More Than Just a Pub

- Ian Hill

- May 27, 2025

- 3 min read

The importance of pubs and beer houses to the sharing of news and information

During the early to mid-nineteenth century the Jolly Farmers transitioned from being a traditional rural farmhouse, brewing and providing beer for its occupants, employed and casual farm labourers, to a legally licensed beer house. But like many rural beer houses and pubs, it became more than just somewhere to drink and eat. It became a communal space where people could get together and discuss issues of the day, gossip, exchange information, conduct formal meetings and business transactions.

In rural areas, access to news was often limited because people just didn’t travel far, indeed there are many well documented examples of people who lived and died without ever having left the parish in which they were born. So, pubs and beer houses played a crucial role as hubs for news dissemination and information sharing, especially among immobile populations with limited literacy.

By the mid-19th century, when Robert Martin Palmer took over the Jolly Farmers from James Herrington, while literacy rates were on the rise, a significant portion of the rural population, including Soham Cotes remained illiterate. This has been evidenced by analysing marriage registers, where the ability to sign one's name was often used as a baseline indicator of illiteracy. According to data from an 1840 report, approximately 67% of men and 51% of women were able to sign their names (1), however this data must be treated with caution because it was relatively common for someone to be able to sign their name but not be literate enough to read a newspaper.

Rural Pubs and Beer houses were accessible and welcoming places for the labouring class, offering a space where news could be discussed freely. The convivial atmosphere, combined with the availability of newspapers, made them ideal locations for the dissemination of information. During the early 19th century, newspapers were heavily taxed, with stamp duties, paper duties, and advertisement taxes, collectively known as ‘knowledge taxes’ and as a result were very expensive, certainly for an agricultural labourer. To put this into perspective, in 1802 and 1815, the tax on newspapers was increased to three pence and then four pence, which was more than the average daily pay of a working man (2). Even by June 1855 when The Daily Telegraph was first published, it cost two pence, against an average daily wage of just over a shilling, which even by then was barely subsistence level. Pubs often provided a newspaper as a means for drawing in patrons, which in turn facilitated communal reading sessions. In many cases, a literate individual would read the news aloud to others, fostering group discussions and ensuring that those unable to read could stay informed. This practice was particularly prevalent in rural areas where access to news and other forms of mass communication was limited and underscores the importance of pubs in the distribution and discussion of news among rural populations and as venues for political and social discourse. This communal nature of pubs and beer house gatherings allowed for the exchange of ideas and discussions on various topics, contributing to the social and political awareness of rural communities.

Like many rural beer houses and pubs, the Jolly Farmers served a multitude of services to the local community, such as that of unofficial community centres and courts. Soham Cotes was only a small rural community, some 2 miles from Soham itself, with around 10-12 dwellings and 40-50 inhabitants, but the Jolly Farmers would have served and been the centre of a much wider and dispersed community of fen cottages and dwellings.

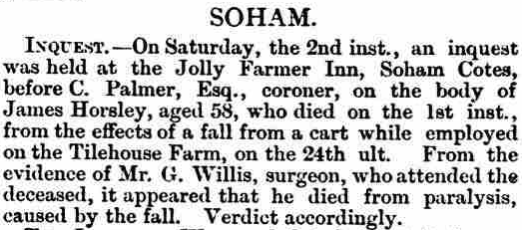

Coroners’ inquests were often held at pubs, and on Saturday 2nd April 1887 an inquest was held at the Jolly Farmers regarding the death of a James Horsley, employed at the nearby Tilehouse Farm, who fell from his cart.

By our modern standards, it is hard to imagine the environment that rural labourers of 18th and 19th century Soham Cotes lived in. Harsh working conditions, cold dark winters, often in damp tiny single room dwellings, no electricity, running water, radio, TV or Internet, in essence cut off from the world around them, living a barely subsistence level existence. To them, the Jolly Farmers would have been a welcoming environment, with light, a warm fire, ale, food, companionship and discourse.